Wilms’ Tumour (nephroblastoma)

Introduction:

Wilms’ Tumours (WT) or nephroblastomas are the most common intra-abdominal tumours of childhood and second most common extracranial solid tumour of childhood (after neuroblastoma). They are derived from mesodermal blast cells, epithelial cells and mesenchymal tissue forming a myxoid stroma. Around 80 children in the UK develop a WT each year. It is equally common in both sexes and most commonly diagnosed in children aged 2–3 years. It was first described by Max Wilms in 1899.

Signs & Symptoms:

Most commonly WTs present asymptomatically. They may be incidental abdominal masses found by parents, for example, when bathing their child. They can also present with clinical signs and/or symptoms. These can include abdominal pain (25%), haematuria (15%), urinary tract infections, varicocele, fever (10%) and anaemia. Hypertension is present in around 25% of cases and Von Willebrand disease is present in 1-8% of patients. Both hypertension anad von Willebrand disease resolve once the tumour has been treated.

If metastatic disease is present, then dyspnea or tachypnea may be present.

Wilms tumours are associated with a number of genetic conditions. Diagnosis of one of these conditions should prompt clinicians to be suspicious of underlying tumours. WAGR (Wilm’s Tumour, anidria, genital abnormalities and intellectual disability) and Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome (characterised by macrosomia, macroglossia, hemihypertrophy, omphalocele and visceromegaly) are two of the associated genetic syndromes. Others include diffuse hyperplastic perilobar nephroblastomatosis (DHPN), Denys–Drash syndrome, Perlman syndrome and Li–Fraumeni syndrome.

Investigations:

Imaging:

Imaging:

Imaging plays a main role in diagnosis and assessment of WTs. Childhood Cancer and Leukaemia Group (CCLG) guidelines recommend:

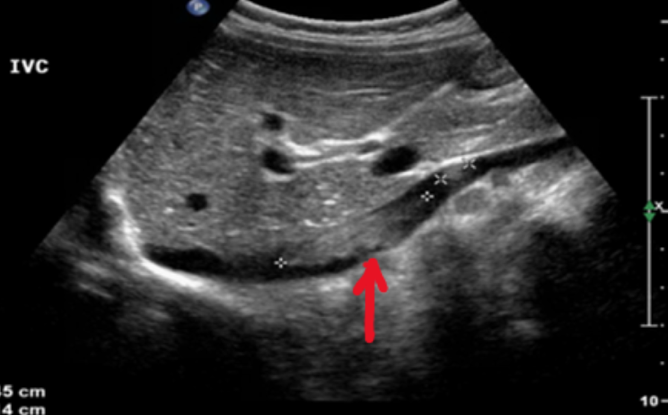

Abdominal ultrasound may be used initially, to include both kidneys, looking for evidence of tumour within the renal vein or IVC and exclude liver metastases

MRI is now seen as the gold standard of imaging for operative planning; this may not be possible in very young children. In this case, CT with doppler US is adequate.

Chest X-ray as baseline for follow up and to visualize large lung lesions. Chest CT is advised if there is any doubt regarding the CXR.

Other investigations include:

Blood pressure and urinalysis (catecholamines, protein and glucose)

FBC, U&Es, LFTs, Coagulation Screen (including von Willebrand factor), calcium, LDH, blood group and viral screen.

DMSA scan if bilateral renal lesions or if partial nephrectomy is planned

Biopsy:

The International Society of Paediatric Surgical Oncology (IPSO) guidance states a patient with suspected WT, of typical age with typical imaging findings will not require a diagnostic biopsy. The rationale for this is that it will not change therapy, may delay initiation of therapy and is unreliable for diagnosing anaplasia.

A renal biopsy should be considered when other (non-WT) differentials of a renal mass are considered more likely. Clinical features such as; age greater than 7 years, raised urine catecholamines and unusual imaging features e.g. numerous calcifications or vascular encasement may prompt a consideration of non-WT diagnosis and therefore biopsy. In cases when age is less than 6 months or greater than 16 years, biopsy is not usually performed and primary nephrectomy is recommended.

USS guidance is recommended when biopsy is performed.

Anterior approach is preferred so that the biopsy tract can be excised at the time of nephrectomy.

It is recommended to take several core biopsy samples to ensure adequate material for the pathologist.

Consider a co-axial technique to reduce the number of entry points into the tumour.

Histological findings:

The typical histological appearance of a WT is a triphasic pattern of epithelial, stromal and blastemal components. The proportions of each of these components varies greatly and biphasic or monophasic tumours are not uncommon.

Anaplastic WT account for 5-8% of all WT. Patient’s with anaplastic WT are generally more likely to be older than patients with non-anaplastic WT. Diffuse areas of anaplasia are regarded as unfavourable histological features. Anaplastic WTs also tend to express p53 and have mutations of the TP53 gene. TP53 mutations have been shown to have poor effects on patient’s survival and therefore, along with diffuse anaplasia, has potential as a poor prognostic indicator.

Treatment:

Surgery is the mainstay treatment option for Wilms Tumours. Other treatment options include pre-operative chemotherapy, post-operative chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

Pre-operative chemotherapy:

CCLG promote upfront pre-operative chemotherapy in all patients over 6 months of age to reduce tumour size, prevent intra-operative spillage and increase the number of children with a lower tumour stage therefore requiring less overall treatment.

For localised, unilateral tumours a combination of Vincristine and Actinomycin D are used for 4 weeks. Re-imaging should be planned for week 4 and surgery should be planned for week 5 or 6.

For metastatic tumours, Vincristine, Actinomycin D and Doxorubicin should be used for 6 weeks. Re-imaging should be planned for week 6 and surgery should be planned for weeks 7 or 8.

For Bilateral tumours a similar protocol as described above is used. Chemotherapy should continue however for as long as there is adequate tumour response.

For children less than 6 months in age, the IPSO does not recommend pre-operative chemotherapy. This is for a few reasons:

- Most tumours in this age group and small and require no further treatment after nephrectomy.

- Mesoblastic nephroma usually occurs in babies. This is a benign tumour requiring no further treatment.

- Actinomycin D can cause serious side effects for newborn or young babies.(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2809467/)

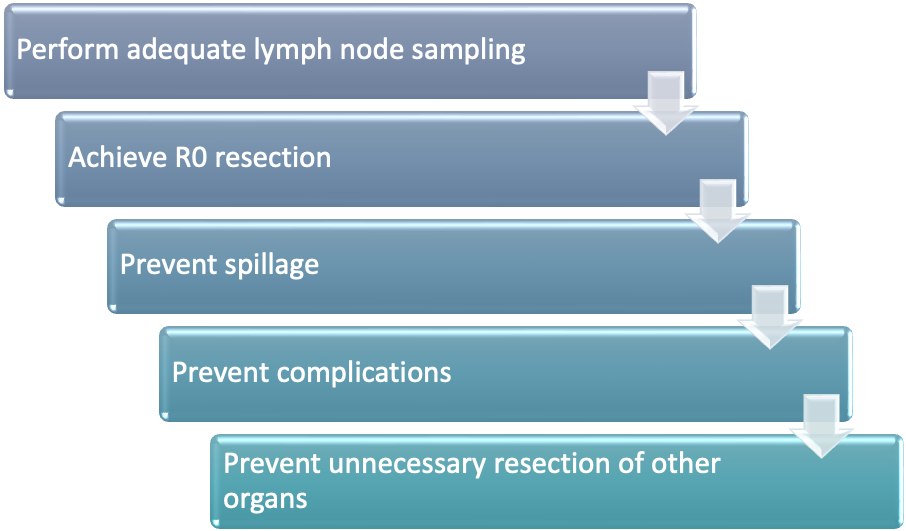

Surgical Goals:

Incision and access:

A transverse or subcostal abdominal incision is performed. Thoracoabdominal incisions can be considered for large upper pole tumours growing posterior to the liver however these incisions are associated with greater complications. The relevant retroperitoneal space is accessed after reflection of the colon and small bowel to expose the relevant renal bed.

Vascular control:

Early control of the renal vessels should be a primary operative aim. CCLG recommends ligating the renal artery first to avoid tumour swelling and increased propensity to rupture. IPSO suggests it may be easier to control the anteriorly positioned renal vein. Ultimately, so long as both vessels are controlled expeditiously, it is not likely to be consequential which is ligated first.

Tumour Resection and node sampling:

The tumour should be removed along with its capsule, Gerota’s fascia, and any other invading tissue or structures. The adrenal gland should be left so long as there are adequate margins between the tumour and the gland. The ureter should be resected as close to the bladder as possible. Hilar and para-aortic nodes (at the region of the renal arteries) should be sampled, even if there is no suspicious characteristics. At least 7 nodes should be sampled. If there is any evidence of tumour spread to lymph nodes, these nodes should be fully excised without causing rupture. Recent studies revealed a higher incidence of tumour recurrence in patients who did not undergo lymph node sampling, which suggests inadequate staging led to under-treatment of the disease. Therefore, sampling of lymph nodes is imperative for accurate staging of the tumour and therefore subsequent treatment

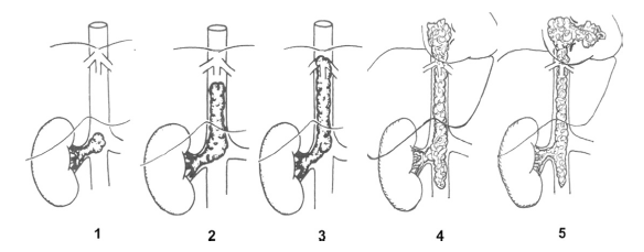

Tumour Thrombus Extension:

Tumour thrombus extension occurs in approximately 8% of patients. These can involve the renal vein alone, infra-hepatic vena-cava (VC), intra-hepatic, supra-hepatic or right atrial. Patients should undergo neo-adjunctive chemotherapy should the thrombus extend into the VC. Thrombus which affects only the renal vein can be resected along with the renal vein. Those infiltrating the infra-hepatic VC should undergo a cavotomy if the IVC is not completely occluded. If completely occluded, cavectomy should be performed. Cava replacement is not required as the collateral circulation that will have been naturally established prior to surgery will continue to serve it’s purpose. For intra-hepatic, supra-hepatic and right atrial thromboses, cardiac and vascular surgeons along with cardiopulmonary bypass are likely to be required. Radiotherapy is a suitable option if the thrombus is not resectable.

Metastatic Disease:

Those with metastatic disease should undergo radiotherapy prior to any attempt at resection. In certain circumstances, such as necrotic tumours or extensive scar tissue rending radiotherapy ineffective, resection may be more suitable. Lung masses should be excised if possible either as radical wedge resection or lobectomy. Sampling of hilar and peri-hilar lymph nodes are as important as for local disease and therefore the same principles should be adhered to. For isolated liver lesions a wedge resection should be explored. For extensive disease it may be more suitable to explore further chemotherapy options in conjunction with an oncologist.

Partial nephrectomy:

Partial nephrectomy for unilateral WT could be considered in selected cases and where the surgical expertise is available. CCLG gives some guidance on when partial nephrectomy may be suitable, however the advantages and risks have to be carefully weighed up for each individual case.

| Indications for partial nephrectomy in unilateral WT. | Contra-indications for partial nephrectomy in unilateral WT. |

| Tumour restricted to one pole of kidney or peripheral at mid-kidney (<300ml volume) | Pre-operative tumour rupture |

| Excision can be performed with oncologically safe margin | Tumour infiltrating extra renal structures |

| Kidney remnant has useful function | Intraabdominal metastases or lymph nodes seen on preoperative imaging |

| Thrombus in the renal vein or vena cava | |

| Tumour involving more than 1/3rd of the kidney | |

| Multifocal tumour | |

| Central location Kidney remnant has useful function |

Bilateral recommendations:

Bilateral cases should be treated as individual cases. The aim should be for bilateral partial nephroectomies preferably 1-2 weeks apart. Complete nephrectomy on one side and partial on the other is acceptable however in some cases bilateral total nephrectomies may be the only option. In these cases, vascular access for dialysis should be placed at the time of surgery. Peritoneal dialysis is an option, but would unlikely be suitable in the immediate post operative period. Transplant should be planned after 2 years of disease free survival.

Post-operative chemotherapy for localised disease:

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | |

| Low risk | No further treatment | AV2 | AV2 |

| Intermediate risk | AV1 | AV2 | AV2 + flank radiation |

| High risk | AVDloc | HRloc | HRloc + flank radiation |

| High risk diffuse anaplasia | AVDloc | HRloc + flank radiation | HRloc + flank radiation |

AV1: Total duration of 4 weeks. Vincristine & Acintomycin D.

AVDIoc: Total duration of 27 weeks. Vincristine, Acintomycin D and Doxorubicin

AV2: Total duration of 27 weeks. Vincristine & Acintomycin D.

HRloc: Total duration of 34 weeks. Alternating courses of Cyclophosphamide & Doxorubicin, and Etoposide & Carboplatin

Post-operative chemotherapy for metastatic disease:

| Histology Standard Risk | Histological High Risk | |||

| Local Stage I and II | Local Stage III | Local Stage I | Local Stage II and III | |

| In metastatic complete response | AVDm | AVDm Flank RT | HRm Pulmonary RT Except blastermal | HRm

Flank and pulmonary RT (except stage and blastermal subtype) |

| Residual metastatic disease | HRm Pulmonary RT | HRm flank RT and pulmonary RT as indicated | ||

AVDm: Total duration of 27 weeks. Vincristine, Acintomycin D and Doxorubicin

HRm: Total duration of 34 weeks. Alternating courses of Cyclophosphamide & Doxorubicin, and Etoposide & Carboplatin

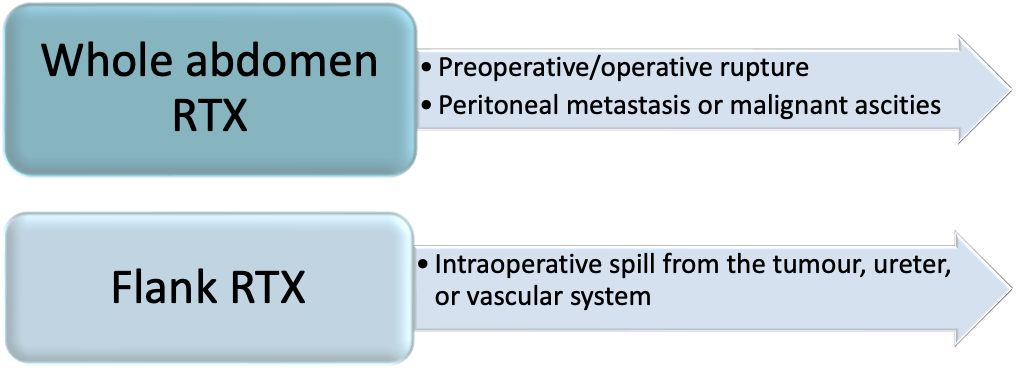

Role of Radiotherapy in Wilms Tumours:

Radiotherapy can be used in the treatment of Wilms Tumours. It can either be focused on the flank, on metastatic sites, or generalised to the whole abdomen. The decision to use radiotherapy in treatment of Wilms Tumours depends on if there has been a suspicion of tumour seeding, tumour rupture, peritoneal deposits or ascites with malignant cells.

Radiotherapy can be used in the treatment of Wilms Tumours. It can either be focused on the flank, on metastatic sites, or generalised to the whole abdomen. The decision to use radiotherapy in treatment of Wilms Tumours depends on if there has been a suspicion of tumour seeding, tumour rupture, peritoneal deposits or ascites with malignant cells.

Staging:

Staging in the UK, as described by the CCLG, follows that of the IPSO as outlined below. It should be noted that these stages are determined after pre-operative chemotherapy (if indicated). It should be noted that the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) differs slightly on their description of staging however both protocols report similar survival rates. Initial staging is based on radiological findings and then supplemented by surgical findings. A more detailed description of staging can be found in appendix 2.

Stage 1 – tumour completely within renal capsule.

Stage 2 – tumour breached capsule or entered renal sinus but completely resected.

Stage 3 – disease limited to abdomen but incompletely resected or spread to abdominal nodes.

Stage 4 – metastatic spread (lungs and liver usually).

Stage 5 – bilateral tumour.

Appendix 1: Risk as described histologically

LOW RISK TUMOURS:

Mesoblastic nephroma

Cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma

Completely necrotic nephroblastoma (100% necrosis)

INTERMEDIATE RISK TUMOURS:

Nephroblastoma – epithelial type (<66% necrosis)

Nephroblastoma – stromal type (<66% necrosis)

Nephroblastoma – mixed type (<66% necrosis)

Nephroblastoma – regressive type (66-99% necrosis)

Nephroblastoma – focal anaplasia

HIGH RISK TUMOURS:

Nephroblastoma- blastemal type

Nephroblastoma- diffuse anaplasia

Clear cell sarcoma kidney

Rhabdoid tumour kidney (treatment recommendations now according to EuRhab protocol)

Appendix 2: Staging as described by IPSO

| Stage 1 | – The tumour is limited to kidney or surrounded with a fibrous pseudocapsule if outside of the normal contours of the kidney. The renal capsule or pseudocapsule may be infiltrated with the tumour but it does not reach the outer surface, and it is completely resected (resection margins ‘clear’)

– The tumour may be protruding (‘bulging’) into the pelvic system and ‘dipping’ into the ureter (but it is not infiltrating their walls) – The vessels of the renal sinus are not involved – Intra renal vessel involvement may be present |

| Stage 2 | – The tumour extends beyond kidney or penetrates through the renal capsule and/or fibrous pseudocapsule into peri-renal fat but is completely resected (resection margins ‘clear’)

– Tumour infiltrates the renal sinus and/or invades blood and lymphatic vessels outside the renal parenchyma but it is completely resected – Tumour infiltrates adjacent organs or vena cava but is completely resected |

| Stage 3 | – Incomplete excision of the tumour which extends beyond resection margins (gross or microscopic tumour remains post-operatively)

– Any abdominal lymph nodes are involved – Tumour rupture before or intra-operatively (irrespective of other criteria for staging) – The tumour has penetrated through the peritoneal surface – Tumour implants are found on the peritoneal surface – The tumour thrombi present at resection margins of vessels or ureter, transsected or removed piecemeal by surgeon – The tumour has been surgically biopsied (wedge biopsy) prior to pre-operative chemotherapy or surgery. |

| Stage 4 | Haematogeneous metastases (lung, liver, bone, brain, etc.) or lymph node metastases outside the abdomino-pelvic region |

| Stage 5 | Bilateral renal tumours at diagnosis. Each side should be sub staged according to above classifications. |

Matthew Newman

Hany Gabra