Chest Wall Deformity

Ms. Kate Burnand

Ms. Kate Burnand

Consultant Paediatric Surgeon,

St George’s Hospital, London

Background and Overview

Pectus deformities represent a relatively common spectrum of anterior chest wall deformities. In fact, they have been reported with increasing incidence, perhaps with the advent of social networking and the availability of less invasive surgeries/techniques to treat them.

There are two main types of deformity: Pectus Excavatum (sunken/hollow chest) and Pectus Carinatum[1] (pigeon chest) but there are also other less frequent types or ‘mixed’ pectus deformities. The incidence of pectus excavatum is roughly 1 in 400 whilst the incidence of pectus carinatum is 1 in 1500. Boys are affected four times as often as girls.

Chest wall anomalies do appear to run in families with 25% of patients reporting another affected family member. Both conditions are thought to be due to an abnormal growth of the costal cartilages. They can be present from birth but often the condition becomes more pronounced around puberty.

They are most often found in isolation but can be associated with other musculoskeletal conditions (scoliosis, kyphosis and Poland syndrome), connective tissue disorders (e.g. Marfans, Ehlers Danlos syndromes) and some rare genetic conditions (e.g. Noonan syndrome). They can also be acquired following thoracic surgery as a child.

NHS Commissioning

As of 2019 NHS England decommissioned all routine surgery for Pectus on the NHS; namely the minimally invasive pectus (Nuss) bar insertion and the Ravitch procedure. Individual funding requests can be completed but the majority of these have not been successful as the published policy did not find justification for the surgery on the NHS from either a psychological or physical standpoint. This has left some individuals and families with difficult decisions as the surgery costs between £10,000 and £20,000.

Bracing for pectus carinatum and vacuum bell therapy for pectus excavatum can still be delivered on the NHS.

Pectus Excavatum

Pectus Excavatum is the most common chest wall deformity. There has been a lot of discussion amongst health care professionals as to whether this condition can cause significant symptoms and signs. Patients commonly complain of chest and back pains which can sometimes get worse with exercise. Other less frequent symptoms include breathlessness, syncope and palpitations (perhaps due to the position of the heart within the thorax). Often the psychological impact from the appearance of this condition is the biggest reported concern.

Diagnosis and work up usually involves clinical examination, clinical photography, lung function tests and chest CT/MRI. If there are cardiorespiratory concerns, extended tests such as echocardiography, ECG and cardiopulmonary exercise tests may be necessary. It is useful to do a focused quality of life questionnaire for a baseline assessment and also to guide whether referral to a psychologist would be beneficial.

Dr Donald Nuss, a South African surgeon working in Virginia, USA presented his innovative technique at the American Pediatric Surgery Association (APSA) in May 1997. Those in the audience describe having their breath taken away, not only because of the revolutionary nature of the new minimally invasive technique, causing less blood loss and shorter operating times; but also the fact that he was presenting his work after he already had 10 years of experience with the technique.

See http:// www.nussprocedure.com/

In certain select circumstances such as mixed deformity the Nuss procedure may not be appropriate. The Ravitch procedure, first described in 1949, may be an option. This involves open resection of abnormal costal cartilages attached to the sternum, enabling this to be mobilised and flattened with or without sternal osteotomies. In pectus excavatum a metal strut can then be placed behind the sternum to help stabilise it. The extent of the operation will depend on the child’s condition.

Both the Nuss and Ravitch procedures have been decommissioned by NHS England as of 2019. Other non-surgical and surgical options have been proposed without long-term proven results.

Areas of Controversy

Patient workup

The diagnosis of pectus excavatum is a clinical one. It is important to assess if it is

- Symmetrical/asymmetrical deformity

Look for mixed deformity – pectus arcuatum – sternal abnormality rather than an overgrowth of the costalchondral cartilages

- Rib flaring – (difficult to correct with surgery)

Scoliosis (especially >300– may warrant input from spinal surgeons prior to any chest intervention)

- Associated conditions

Such as that for Marfan’s syndrome – workup according to modified Ghent criteria, Poland syndrome etc.

- Poor posture – often known as ‘pectus posture’

This is typically rolled shoulders and lumbar lordosis attributed to a shortening of the pectoral muscles, this is something that can be improved with physiotherapy alone.

For a child who comes to clinic and has no signs of cardiorespiratory compromise or pain, an explanation and reassurance is probably all that is needed, there is little point in any further investigations since the NHS has cut all commissioning for surgery.

- Imaging

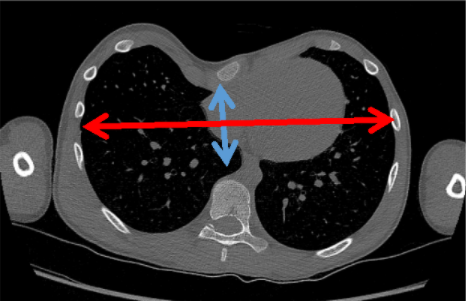

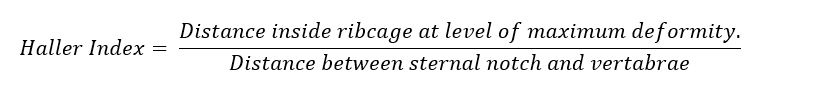

X- rays (AP and lateral) can be helpful for assessing the degree of excavatum and also for assessing scoliosis. If surgery is to be planned a non-contrast CT scan of the chest is more sensitive for assessing the severity of the condition using the Haller index, sternal rotation and cardiac displacement. The Haller index (HI) (created in 1984 – by an American surgeon, Alex Haller) is a crude objective measurement for assessing the severity of the PE. A Haller Index of 2.5 is considered normal, a Haller Index of > 3.2 is considered pathological.

If any symptoms or associated syndromes (e.g. Marfan’s) are present pulmonary function tests or echocardiography may be indicated. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) may prove to be the most sensitive test for detecting functional consequences of physiologic impairments due to PE. There is a follow up study of adolescents who have undergone CPET tests before, 1 year and 3 years following surgery. This shows that cardiac index was reduced compared with controls prior to surgery, however after Nuss bar removal and 3 years post-surgery the CPET results returned to the normal.

- Psychological input

Children with chest wall anomalies seek a specialist medical opinion due to concerns over physical symptoms, chest appearance or both. Formal evaluation of perceived body image and quality of life may be as or more important than the cardiorespiratory workup.

There is a myriad of evaluation tools. The Pectus Excavatum Evaluation Questionnaire (PEEQ) is a focused, validated, 24 question survey regarding physical symptoms and body image. The pre-surgical psychological score does not reflect the objective severity of pectus (Haller index), however following surgery there is a significant improvement in the overall score. Other more generic quality of life scoring systems have been used such as Child Health Questionnaire for patients (CHQ-CF87) and their parents (CHQ-PF50).

We use the 12 question child PEEQ questionnaire as a screening tool for all our children over the age of 12 years of age not only to elicit those children with a low score but also highlight children who have quite a mild deformity objectively but have a very low self-esteem regarding their body image (in keeping with a body dysmorphic disorder). These children all get referred to a psychologist for assessment.

Age of surgery

Historically, many surgeons used to advocate for early repair. For instance, in Nuss’s original series of 42 children the median age of insertion of the pectus bar was 5 years. At this stage the surgery is technically easier as the chest wall is very pliable, and it avoids any psychological distress related to body image which typically becomes apparent in adolescence.

Nowadays most surgeons typically offer pectus bar insertion after the onset of puberty due to concerns regarding:

- Acquired asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy – if a repair (particularly Ravitch) is performed at a young age.

- Recurrence is more common as the chest wall continues to change through puberty with accelerated growth of costal cartilages compared to ribs.

- Inability of the young child to consent or be Gillick competent.

- Many patients may remain asymptomatic and suffer for minimal/none psychological distress.

- Severity of pectus excavatum typically only becomes apparent at puberty.

Sternal elevation

There have been a number of modifications to the surgical procedure since it was first described by Nuss. He did not include thoracoscopy for instance. This, however, this has become an integral part to the procedure especially to try and minimise complications. There is now an expectation to obtain a ‘critical view’. The critical view consists of:

- Always visualising the dissector/introducer’s tip

- Clear view across chest with the pericardial sac away from the sternum

- The contralateral exit site should be visible before the introducer is passed

It is usually possible to obtain the ‘critical view’ with thoracoscopy when the optical port is placed in a low lateral position and a 30° scope is used. It is sometime necessary to actively elevate the sternum so the ‘excavatum’ is not blocking the view.

There are various options for sternal elevators:

- Bilateral Langenbeck retractors pulling up on entire chest (Fig. 5)

- T fasteners

- Volkmann bone hook (Fig. 6)

- Sternal wire (trans-sternum) being attached to a table-mounted clamp (Fig. 7)

- Sternal clamp

Other options

A non- surgical treatment for pectus excavatum is vacuum bell therapy (VBT). This is placed on the thorax and a negative pressure is generated by means of a hand pump connected to the vacuum bell. This is activated daily/multiple times a day by the patient. A systematic review revealed that the VBT is safe and can generate some good results particularly in children with mild/moderate deformity and compliant chests. The efficacy of the treatment in the long term is unknown.

Filling techniques such as custom-made pectus implants or autologous fat transplants are now also available. These methods do not affect the rib cage themselves. Silicone implants can be created specifically for the individual based on a 3D scan of the body. They are placed above the sternum under the pectoral and abdominal recti muscles and are inserted through a small midline incision. Lipo-filling which involves autologous fat transfer is only suitable for mild cases, in an individual who has sufficient fat reserves (often these patients are thin), can involve several injections and can have variable results which may diminish over time.

Useful papers

- Clinical Commissioning Policy: Surgery for pectus deformity (all ages), published https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/1675-Policy_Surgery-for-pectus-deformity.pdf

They sum up the evidence for both physical and psychological arguments for offering surgery and fall in support of decommissioning it from routine NHS practice. This does not apply to vacuum bell treatment for pectus excavatum or bracing for pectus carinatum.

- Nuss D, Kelly RE Jr, Croitoru DP, Katz ME. A 10-year review of a minimally invasive technique for the correction of pectus excavatum. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(4):545-552. doi:10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90314-1

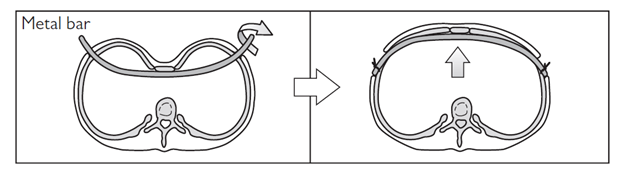

Original series of the pectus bar patients first presented in APSA 1997 but published in 1998. It looked at 42 children who had undergone the novel procedure. Rather than cut and resect cartilages as in the Ravitch procedure, this operation involved placing a convex steel bar through two lateral incisions in the chest wall, behind the sternum and flipping it through 180 degrees to remold the chest. The bar is removed after 2 years. Even in this trial series Nuss adapted the technique due to bar displacement and imperfect cosmesis. They increased the length of the bar and also used two bars where necessary. Interestingly the median age of this pilot series was 5 years of age which is obviously different from modern practice.

- Patel AJ, Hunt I. Is vacuum bell therapy effective in the correction of pectus excavatum? [published online ahead of print, 2019 Mar 28]. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2019 ; ivz082. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivz082

Systematic review of 1005 patients who had undergone VBT for pectus excavatum. The outcomes of eight papers have been reviewed. The protocols were all different and the follow up periods limited but it seemed to be successful for the short term particularly in compliant symmetrical pectus excavatum chests.

- Lawson ML, Cash TF, Akers R, Vasser E, et al. A pilot study of the impact of surgical repair on disease-specific quality of life among patients with pectus excavatum. J Pediatr Surg. 2003 Jun;38(6):916-8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00123-4. PMID: 12778393.

A pilot study for a disease specific quality of life questionnaire for pectus. This particular study carried out a 12 point questionnaire on both children and their parents at three time points: pre pectus surgery, 6 and 12 months after surgery. This initial study only published questionnaire results from 19 children and 22 parents.It had subsequently been validated by tow different groups and has been modified for adults.

- Maagaard M, Tang M, Ringgaard S, Nielsen HH, et al. Normalized cardiopulmonary exercise function in patients with pectus excavatum three years after operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013 Jul;96(1):272-8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.03.034. Epub 2013 May 14. PMID: 23684487.

75 adolescents followed up – had CPET testing preoperatively, at 1 year and 3 years after Nuss Bar insertion. They had a significantly lower cardiac index preoperatively than normal controls and this improved 1 year after surgery and returned to normal 3 years after surgery and after Nuss bar removal.

Curated by Mark Davenport, [email protected]

[1] Carinatum is nothing to do with pigeons – but refers to carina, Latin for keel (of a boat).